- Home

- Shepard, Sara

The Heiresses Page 4

The Heiresses Read online

Page 4

Aunt Penelope leaned on the cane she’d used ever since her skiing accident. Rowan’s mother set down her water glass. “Are you seeing someone, Ro?”

“Oh, we’re just friends,” Rowan said quickly.

Aunt Candace and Aunt Penelope exchanged a glance, as if to say, Oh, no. What’s wrong with this one?

Rowan’s skin prickled, and sensing more questions on the way, she excused herself, darting into the hall. She hurried past the line of Warhols, Picassos, and an Annie Leibovitz portrait of Poppy’s parents, her mom in a long, breezy dress, her strapping, tanned father in jeans and a polo shirt, in front of a ramshackle red barn. They’d always been Rowan’s favorite aunt and uncle. In middle school she’d spent several summers on their farm, shearing the sheep with Poppy and exploring the cavernous attic in their refurbished farmhouse. Uncle Lawrence hadn’t gone into the family business, but he had several old photo albums of the family from back before Papa Alfred found the Corona Diamond. Rowan and Poppy used to marvel at snapshots of Edith without her now-ubiquitous fur.

When she reached the bathroom, Rowan slipped inside and slammed the door hard. A little wooden plaque hanging from the doorknob rattled. “Go Away,” it read. Rowan’s thoughts exactly.

Rowan stared at her reflection in the mirror. She had a long, oval face, bow-shaped lips, a long forehead, a sloping nose, and the signature Saybrook blue eyes. Her tall frame was lithe and toned from long runs and hours on the tennis court. She knew she was pretty; plenty of people said so. And she was as successful as Poppy said—senior counsel at Saybrook’s just five years out of law school, and she sat on several review boards and charities. She loved her family, and she adored her two dogs, Jackson and Bert. But she was nearly thirty-three, and still on her own.

It was, of course, the same conundrum she’d pondered for years. Thanks to her two older brothers, who had chosen not to go into the family business and now lived across the country and overseas, Rowan had no trouble with men. Growing up, she was always up for a game of hockey or freeze tag at the end of their cul-de-sac in Chappaqua, and she beat up on Michael and Palmer as much as they beat up on her. As she got older, she and some of her cute guy friends did more than just play touch football. Girls in her class talked about only having sex when they were in love, but Rowan thought that was just about as naive as believing that putting on a satin gown made you Cinderella.

Of course, in time those were the girls who got steady boyfriends, while Rowan had just acquired a string of make-out buddies. She tried to change her ways, copying what she saw in the paired-up girls she knew, but becoming a softer, needier, whinier version of herself just didn’t work. And so she settled into the role of the quintessential guy’s girl. The one who’d go to a strip club on a lark. The one who’d match you shot for shot. The girl who didn’t give a shit about getting mani-pedis with her girlfriends, who didn’t care if porn was on, who almost seemed like she didn’t need a guy.

It didn’t mean Rowan didn’t want what those other girls had. But now, she felt too old to change who she was—nor should she have to. Her parents didn’t give Rowan a hard time about being single. Her mother, Leona, had been an essayist in her past life, exploring open marriages and same-sex rights—much to Edith’s embarrassment. Her father, Robert, treated Rowan the same as his sons, pushing her to be ambitious and successful over everything else. And her brothers always told her not to settle. It was Poppy who eagerly shoved eligible guy after eligible guy Rowan’s way. Though they were nice and cool and Rowan had remained friends with quite a few of them, none of them exactly . . . clicked. Rowan had felt true love once before, and she wouldn’t settle until she felt it again.

There was a knock on the bathroom door, and Rowan looked up.

“Rowan?” someone whispered. “You in there?”

Rowan opened the door a crack and saw James’s curly brown hair, light eyes, and slightly crooked smile. “No fair that you get to hide out in here,” he said mock-sternly.

James’s skin smelled like peppermint soap. A fleck of glitter from one of the princess’s wands was stuck to his cheek. Rowan refrained from brushing it away.

“I just needed a minute,” she told him.

He glanced down the hall. “Princesses getting you down? The grown-up ones, I mean?”

Rowan stared at the monogrammed towels hanging on the silver bar across the room. One bore Poppy’s initials, the other, James’s. “You could say that.”

“Do you want me to smuggle you out of here, Saybrook?” James asked, his gaze shifting conspiratorially. “We can escape out the balcony. Use the gargoyles as a ladder.”

She pictured the two of them scaling the Dakota, dropping to Central Park West, and falling in with the biathletes. They’d laugh together, like in the old days.

James slipped into the bathroom. “Is there room for another?” he asked, shutting the door. “I’m princessed out too.”

Rowan sniffed. “Please. All the men are just watching tennis.”

James leaned against the sink and made a face. “Have you ever hung out with Mason for any length of time? He’s the biggest princess of them all.” Then he picked up a remote sitting on the edge of the soaking tub and pointed it at a small TV in the corner. “And anyway, we get the match in here too.”

The French Open appeared on the screen. Rowan remained planted in the middle of the bathroom, her arms wrapped tightly around her torso. Though she saw James regularly, she couldn’t remember the last time they’d been alone together.

They’d become friends at Columbia, when they lived on the same floor freshman year. Rowan’s father had offered to buy her an apartment, but she liked the idea of being like everyone else, even opting for a double instead of a single. She’d spent most of the time in James’s dorm room, playing video games and chatting about the people in their building, especially the girls. They’d stayed on for graduate programs at Columbia, James for business school—he had always wanted to be an entrepreneur—and Rowan for law. They had a standing Monday-night dinner date at a Mexican dive on Broadway with spicy guacamole. On weekends, they played pool at SoHa, the dingy bar on Amsterdam whose bartenders made potent Long Island iced teas. As usual, Rowan had fallen into her role as the perennial guy’s girl, James’s wing woman. Plenty of times Rowan had consoled James’s date at the end of the evening when she caught James making out with someone new in the unisex bathroom. If a girl broke up with him Friday morning, he’d have a new fling by Saturday night.

“You’re such a dog,” Rowan had always teased him over brunch on Sunday mornings. To which James just shrugged and bared his teeth. “Woof.”

Now James stared at the mini TV over the tub. It was the third set, the match tied. “Okay, Saybrook,” he began, pointing at the screen. “Djokovic, or Federer?”

Rowan swallowed hard. It was an old game they used to play—one of them would name two people, and the other would have to pick which they’d have sex with. Sometimes it had been a geek showdown, like Sylvia Plath versus Emily Dickinson, or Shakespeare’s Iago versus Oberon from A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Other times they named people in their lives—Veronica, the busty registrar, or Colette, the waifish French exchange student. More often than not, James would actually go home with the hot exchange student.

Sometimes Rowan thought James had forgotten their old friendship entirely, now that he was married to Poppy. Although maybe he didn’t want to remember part of it—especially the part about all the girls. James had reformed for Poppy. Poppy was much too beautiful and perfect for anything less. Any guy would fall in line for her.

Rowan looked at the players on either side of the court. “Federer for sure,” she decided. “Djokovich is too cocky.”

“Tall, dark, and European. I like it.” James tilted his head down, his expression mock-serious. “So tell me: Who do you have on tap these days?”

Rowan pretended to rub out an invisible water spot from the sink. “I plead the fifth. I’ve already been asked that question a few too many times today.”

James sank down to the edge of the tub. “You have to give people a chance, Saybrook. Actually go out with someone more than once.”

“I go out,” Rowan insisted.

“I know you do.” James laid his hands in his lap. “But who have you actually liked?”

Rowan stared intensely at the TV screen, trying to recall the last time she’d last gone out with someone consistently. Someone she’d actually felt something for.

“See? You can’t even remember.” James playfully nudged her calf with his toe. “They can’t all be like me, you know,” he said, spreading his arms wide and giving her a boyish grin

Rowan froze. He was kidding, wasn’t he? Her pulse thudded in her palms.

Five years ago, when they were at SoHa just before finals, James had taken a deep breath and looked at Rowan over his beer. “So, Saybrook. I was thinking about checking out this Meriweather place you always talk about.”

“Oh?” Rowan cocked her head. “Do you want to visit? There’s room.”

“Actually . . .” James fiddled with the straw in his drink. “I rented a place on Martha’s Vineyard. For the whole summer.”

“What?” Rowan blurted.

James’s gaze bored into her. “Yeah, I was thinking it would be nice to hang out together outside the library or the dive bars.”

His eyes and smile were so damn dangerous, instantly sucking her in. But Rowan knew what he was like. She’d seen him work his magic on other women. And yet when he looked at her, she was just as weak as all the rest. That night, when she went home, she fantasized about the shape their summer would take. The meals they’d cook, the things they’d talk about, the family members he’d meet. And then . . . what? After hours and hours of talking and laughing, in that beautiful setting, with the stars twinkling all around them, what would happen next?

She knew it wasn’t wise to think that way. She was being naive, one of the many pitiful girls who fell under James’s spell. She was afraid of her feelings for James, mostly because how strong they were. But there was such a big if. If James felt the same way, well . . .

She’d thrown him a party the night he arrived. All the cousins, even Natasha, lined up in the foyer to greet him. Poppy strode up first and extended her hand. “Rowan has told me so much about you,” she gushed. “I’m her cousin, Poppy Saybrook.”

“Another Saybrook,” James had said, smiling that wolfish smile, his eyes skimming her up and down. It was the same thing he’d done to countless, countless girls in Rowan’s presence, but something inside Rowan still lurched. He wasn’t supposed to do that here.

That night James gave a toast on the patio, thanking everyone for giving him such a warm welcome, especially his “best friend, Saybrook.” Every time she turned around, he was chatting with Poppy, and soon enough she realized that he wasn’t just being polite. Rowan had to duck behind the bar that had been set up on the edge of the patio to collect herself, feeling that infrequent hot sting behind her eyes. She felt so blindsided. And stupid. To make matters worse, she felt someone staring at her from the other side of the yard. It was Natasha. Her gaze slid from Rowan to Poppy and James—as if she had it all figured out.

Knowing she was going to lose it, Rowan had retreated to a bedroom, sat down on the bed, and stared at the diamond-printed wallpaper, seeking refuge—much as she was now, in James and Poppy’s powder room.

Blinking the memory away, Rowan turned to James and tsked. “If you keep saying things like that, I’m going to have to hide from you too.” She opened the door. “C’mon. We’d better join the royal court.”

The party had moved into the dining room. Streamers and glittering tiaras surrounded the tiered buttercream-frosting cake on the table. Corinne’s mother was placing three little candles in the center, and all the young mothers stood around, oohing and ahhing. Aster had finally appeared, looking tired but still managing a smile. Rowan looked around for Poppy and found her standing in the corner with Mason. Mason’s face was red, and Poppy’s mouth drawn. Rowan had never seen them argue—since Poppy’s parents died, Mason had taken her under his wing, much as Candace and Patrick had, treating her like a third daughter.

They were talking so heatedly that Poppy seemed oblivious to the cake lighting. More important, she didn’t seem to notice that Rowan had just come out of the bathroom with her husband.

But someone else had noticed. Natasha stood at the end of the hall, her head cocked, her gaze squarely on Rowan’s face. She raised one eyebrow, just as knowingly as she had that night Poppy and James met. Rowan looked away, watching James kiss his beaming daughter on the cheek.

They can’t all be like me. Little did James know how true that was. She’d known James for nearly fifteen years, and she’d loved him every minute.

UNCORRECTED E-PROOF—NOT FOR SALE

HarperCollinsPublishers

....................................

4

A few days later, Aster sat down in her parents’ Upper East Side town house for the dreaded but obligatory weekly Wednesday dinner. The enormous table in the baroque-style dining room was set for twelve, with silver candlesticks in the center. The high-backed mahogany chairs were so huge and heavy they could have served as king’s thrones. The blocky, mahogany china cabinet, an heirloom from the eighteenth century, took up a whole wall and bore priceless Sèvres plates, artifacts from her parents’ world travels, and a silver tea set that had once belonged to a queen. There were lots of portraits of dead relatives, landscapes showing a foxhunt on the moors, and a huge painting of Edith and Alfred with their young children, standing on their staircase. On the top step were Mason and Lawrence, Poppy’s dad, both with slicked hair; then Rowan’s father, Robert, and Natasha’s mother, Candace, at the bottom. Candace, probably no more than four at the time, struggled to hold Grace, a fat, grumpy-looking baby. Years ago Aster had loved this room, and made up stories about the people in the paintings and the previous owners of the artifacts. She would tell the stories to her father over breakfast in the morning. He always listened attentively, and laughed at all the right parts. “Maybe you’ll be an author someday, Aster,” he’d tell her. She hadn’t made up stories about the room in a long time.

“Thank you so much, Esme,” Penelope Saybrook murmured as their private chef placed a roasted chicken in a red wine reduction next to a platter of grilled asparagus and Brussels sprouts in the center of the table. As usual, Aster’s mother stood, rearranged some of the garnishes, and added a dash of pepper to the bird. You don’t get to pretend you cooked it just by playing with the pepper, Aster thought.

“Yes, thank you, Esme,” Corinne added. Dixon, who was sitting next to her, nodded his thanks, and Poppy, who was next to Mason, smiled sweetly. Ever since Poppy’s parents died, she’d had a standing invitation to dinner. Sometimes Aster wondered if Poppy’s recent closeness to Mason stemmed from her father’s survivor’s guilt; he was supposed to have been on the plane that killed Poppy’s parents. Usually Poppy brought James and the kids, but today she had come alone. She’d brought with her a homemade strawberry pie, using the berries she’d picked the previous week during a visit to her family’s rural estate in western Massachusetts. Only Poppy, who probably worked twenty-three hours a day, could also find time to bake a pie.

“You rock, Esme!” Aster yelled enthusiastically, adjusting the strap of her jacquard bustier top. Her father eyed it disapprovingly. Whatever—everyone and their grandmother were wearing bustiers these days. Well, except Corinne, who sort of looked like a grandmother in a Wedgwood-blue sleeveless silk dress and Mikimoto pearl earrings.

Aster eyed her sister across the table. Corinne hadn’t even glanced in her direction yet, and Aster certainly wasn’t going to make

the first move. Her gaze then wandered to another portrait on the wall, this one taken about ten years ago. It was of herself, Corinne, Poppy, and all the other first cousins, including Rowan’s brothers, and Aunt Grace’s young sons, Winston and Sullivan, who lived in California with the now-divorced Grace. Natasha was there too, front and center.

Just looking at Natasha irritated Aster. The girl had acted like their best friend for years, hogging the spotlight, begging them to come to every school play she was in, even once dragging Aster to accompany her to an open-call Broadway audition when they were both fourteen years old. And then, just like that, she just . . . didn’t need them anymore. Aster couldn’t believe Natasha was in Corinne’s wedding; Poppy had somehow talked her into it.

“Is that blood?” Aster’s grandmother Edith asked, pulling her mink stole tighter around her shoulders—she never took it off, even though it was May and uncharacteristically warm. Her white hair was slicked back from her face, and her skin showed her good bone structure, the high cheekbones and tiny pert nose that Aster had thankfully inherited. Jessica, the personal-assistant-slash-nurse who accompanied Edith everywhere, leaned over to examine the plate.

Mason, who was thinner now that he was working out with a personal trainer, inspected it as well. “No, Mother,” he said wearily.

“It’s just the sauce,” Poppy added helpfully, taking a bite. “See? Tomato basil, yum.”

Edith considered it for a moment, probably only because Poppy was her favorite granddaughter and she hated to disappoint her. Finally she pushed the plate away. “Well, this is too undercooked for my liking.” She looked accusingly at Penelope, just as she always did when she found fault in something in her daughter-in-law’s house. Penelope snapped for the chef, who rushed to take Edith’s plate away. “I’ll have a soft-boiled egg in an egg cup, please,” Edith brayed loudly.

After the offending chicken was gone, Corinne cleared her throat, tearing her eyes forcefully away from the breadbasket. “So I checked the registry, and a lot of people have donated to City Harvest.”

The Lying Game #4: Hide and Seek

The Lying Game #4: Hide and Seek The Lying Game #5: Cross My Heart, Hope to Die

The Lying Game #5: Cross My Heart, Hope to Die 9780062240149 First Lie

9780062240149 First Lie Pretty Little Liars #13: Crushed

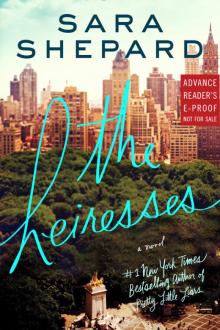

Pretty Little Liars #13: Crushed The Heiresses

The Heiresses